|

BAILE (HOME) BAILE (HOME)

ÁR DAOINE (OUR PEOPLE) ÁR DAOINE (OUR PEOPLE)

SINNSREACHD (ANCESTRAL WAYS) SINNSREACHD (ANCESTRAL WAYS)

ÁR CREIDEAMH (OUR FAITH) ÁR CREIDEAMH (OUR FAITH)

TAIGHDE (RESEARCH) TAIGHDE (RESEARCH)

NASCANNA(LINKS) NASCANNA(LINKS)

|

|

Creideamh |

|

The religious beliefs of Sinnsreachd are inseparable from the culture, but they deserve a good, solid look on their own merits as well. Before reading, it is important to understand two key things about the information on this page- First, this is the theological and ritual way of the Ciarraide, and is not intended to be taken as doctrine for the Sinnsreachd movement as a whole. Each túath will have a somewhat different spin on things- though the overarching bulk of what is presented here is universal to Sinnsreachd, the details will vary. Second, Sinnsreachd is a modern religious and cultural movement. While descended, directly and indirectly in varying ways, from the original pre-Christian faith of the Gael, it is not the result of secret family traditions of hidden �druid cults� or other such nonsense. Neither is it an attempt to reconstruct the faith of our ancestors as they followed, for such would be virtually impossible without the aid of a time machine. We simply do not know every last detail of our ancestors� faith and thus have to work from the core parts that survive in recorded lore and customary traditions. Much survived, enough to build from and reclaim our faith, but it is in a modern incarnation and not a direct continuation of that of our ancestors. It could be likened to the differences between ancient and modern Judaism- the same faith, praying to the same god, with most of the same core cultural and social elements, but also changed by time, loss and recovery or replacement of knowledge, and an expansion of scientific and celestial knowledge. When it comes to discussions of things-Celtic, especially religious beliefs, it is important to recognize a few important facts. First, Ireland and Scotland have been Christian for over a thousand years, and while there were elements remaining and last vestiges of the pre-Christian faith around as recently as the 14th Century, Christianity has vastly influenced Ireland for over 1,300 years. This has had many direct and indirect effects on the study of pre-Christian Gaelic faith, not the least of which has been the vast muddying of the waters in the past century by a variety of people, ranging from unscrupulous authors to nationalists with political agendas. In the quest for truth, it is best if the seeker compare the claims of a group, author, or religion against the basics of language, lore, and literature, all of which can be found through our Research page. Secondly, Sinnsreachd is one religion of one segment of one cultural grouping of the overarching heading of "Celts". There is no unified Celtic belief, and there never was. Sinnsreachd is one of nearly a dozen faiths within Gaelic culture, with many of the rest being variations of Christianity and only a third being polytheistic like our faith. Gaelic culture is further divided up into three overall cultural groups based on regional origin- Éireannach, Albanach, and Manannach- from Ireland, Scotland, and the Isle of Mann respectively. Gaelic culture is one of three surviving Celtic cultures (Gaelic, Brythonic, and Cymric), and one of six (or more) original ones (Gaelic, Brythonic, Cymric, Gallic, Galatian, and Iberian). Each of these cultures varied from each other as much as Plains Indian tribes varied from Pacific Northwest tribes, culturally, religiously, and linguistically. Similar and falling under the same overall cultural grouping, yes, but very different in the details. Anyone trying to sell their wares as a universal "Celtic religion" or similar is flat lying. Lastly, our faith is a living, breathing entity in the modern world, not some anachronistic attempt to recreate the ancient beliefs of our ancestors as they were two millennia ago. Sinnsreachd is for today, for our people now, and embraces modern scientific and cosmological understandings of existence. We understand and accept that the Sun is a burning ball of plasma fed by a hydrogen-to-helium reaction, and not the giant flaming chariot wheel of a deity. However, the core ethics, morals, doctrine, and customs of our people are by and large timeless, and neither require us to live in an Iron-Age mindset nor to shirk an expanded and enlightened understanding of the cosmos. In fact, quantum physics and our expanded understanding of things such as non-corporeal intelligence, the multiverse, string theory, etc. are all complimentary to our beliefs in many ways. We do not need to cast aside science and modernity in order to practice our faith, but instead mold our understanding and practice of such things through the filter of what we believe. The intent of this page is to break from the usual method of presenting our beliefs; to veer away from the archaeo-religious dissertations and discussions of ancient beliefs in favor of explaining how we do things now and will do in the future, and what we believe now as opposed to in the past. In this page we will look at the polytheistic Gaelic belief that is Sinnsreachd- the theology, ethics, principles, rituals, and much more. This page is very, very long and for that I apologize, but I would rather impart a broad range of information rather than a simple five or six paragraph overview. Much of this information has never been presented before, at least not in this venue, and thus it is important to remember that these are the modern beliefs of the Ciarraide and related peoples.

Contents- Sinnsreachd: Traidisiún Sinseartha Spirits and Beings of Our Beliefs

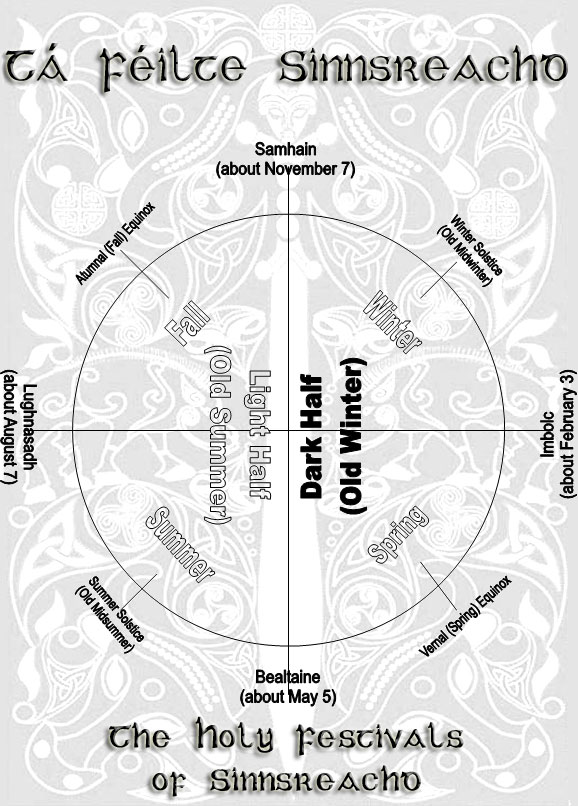

The Ways of Our Ancestors Religion is the core of our culture, intrinsically integrated into the overall body of the culture, but giving it a soul, a connection to the eternal, as well as a binding connection to our ancestors from whom we inherited our way of life. It is this sacral bond that gives strength to our people. Our religious beliefs, called Traidisiún Sinseartha (Sinnsreachd for short), are a practical, spiritual, and primal way of viewing the world that is based in a combination of tribal worldview and familial paradigm. The general tenets of our beliefs can best be explained as answers to a series of questions about the universe around us. Let us start with theology, the nature of the Divine.  What is the nature of the Gods? It is not simply enough to name them and give a basic overview of their place in history, but to fully understand the modern interpretation of our beliefs one must comprehend the basic nature of the Gods. The simplest answer to the question �what are the Gods?�� is that they are a race of supernatural eternal beings capable of creating and shaping reality, souls, and universes, who exist outside of space and time as we know it. They are also our first ancestors, not simply being an ancient race of people who gave birth to us, but the gods who created the very souls that inhabit our bodies. Like our people, the Gods of the Gael, the Túatha de Dannan, are a family-based tribe. It was they who taught our most ancient ancestors the culture and ethics we follow to this day, for our culture is an imperfect reflection of theirs. In a way, our very way of life was created by them and given to us as their legacy. To our beliefs, all gods exist, and are grouped into tribes, each governing a given group of people. If you follow one tribe of gods such as, say, the Hellenic gods, then you live by their rules, are affected by them, go to their created afterlife when you die, and are protected by them from harm by other tribes of gods. In exchange, you follow their edicts and laws, carry out their orders, and provide them with a direct connection to the mortal world. Different tribes of gods have different, and often competing or incompatible ethics and goals, and thus the idea of serving more than one tribe is a very dangerous and undesirous thing. For to serve two sets of masters is an untenable position to be in if those masters take to feuding. The Túatha de Dannan, the gods of the Gael, are the tribe whom we follow. Though there are tribes of gods out there who are similar in ethics and goals to our gods, the Æsir and Vanir, for example, they also have their own agendas that preclude mortals from being able to easily serve them both. Thus it is that we chose to follow one or the other rather than having one foot in two camps, so to speak. The Túath de Dannan are covered more in-depth and individually later on. The paradigm through which we see the divine, not just our gods but all gods, is a belief called Polytheism. As was explained above, we believe all gods exist, but not as aspects of a single deity or an ambiguous �source��, but as distinct and separate individuals with their own personalities and even rudimentary gender concepts. Often, these gods have an auspice, either direct or implied, over certain aspects of existence. In other words, there will be a god of weather, a god of war, a god of the sea, and so on. Within the Gaelic theology, this is a bit more complex. Our gods are not pigeonholed into set, ordered archetypical slots in the celestial machine, but are more like humanity in that they often blur the lines and overlap. Fully one-third of all Gaelic deities are involved in some aspect of war, for example, yet often have other aspects of existence that they are connected to. These aspects are often based around occupations, with a deity who fills that occupation being seen as the patron of all mortals engaged in that pursuit. For example, Goibhniu is the smith and chief brewer of the Túatha de Dannan. As a result, smiths and brewers of the Gael venerate him more highly than, say Macha, the goddess of sovereignty. Other gods of the Túatha de Dannan do not have a specific occupational aspect, and are instead seen as the paragons of a type of person. For example, Nuada is seen as the epitome of the perfect king- fierce and grand in battle, solid and fair in judgment, and a righteous and generous leader. Still others among the Túatha de Dannan have no discernable aspects that would fall into the general understanding of occupation or cosmological patronage, and are generally not venerated for the most part. This brings up the next major point about our beliefs- who are our gods? Now that we have explored the way in which the Gael see our gods, it is time to discuss them as individuals. The Túatha de Dannan come from a race of gods who originated in the realm of Tír na nÓg, the Land of the Young, wherein are found the four great cities- Falias, wherein dwells the great teacher Morfesa, and from which the Lia Fail (the Stone of Destiny) comes, Górias, where Esras the Noble is found, and in which Nuada's sword Freagarthach, the symbol of the Ciarraide, was made, Múrias, where Senias the Wise teaches wisdom, and where the essence of light was forged into Gáe Assail, the spear with which Lugh slew Balor, and lastly Finias, city of Uiscias the fair-haired poet, where Undrí, the Cauldron of an Dagda, was crafted. Only a small number of the Gods came to Mide (one of the names of the mortal realm), with the majority staying behind in their own realm. In order to come to this realm, they had to create avatars, mortal bodies that they inhabited so that they could experience time and space through a mortal�s eyes. This limited their abilities and made them vulnerable to physical need and threats, but they chose to do so in order to shape this world and teach the mortals their ways. Those that came to this realm followed their matron Dannan, also known as Danú, and were thus known as the Tribes of Dannan- Túatha de Dannan. Nuada The great and noble gods of the Túatha de Dannan hold many positions and govern many aspects of the world. The king of the Túatha de Dannan is the great and noble warrior Nuada. Nuada Lámhairgid was the king of the gods when they set out from Tír na nÓg, but lost his position when he lost his arm in battle against the Fir Bolg at Magh Tuiredh. Though the Fir Bolg were defeated, Nuada had to abdicate the position of Rígh as he was not completely whole in his body. Bres Mac Elatha, also known as Bres the Beautiful, took his place and proceeded to tyrannize the Túatha de Dannan. After a while, his excesses, lack of hospitality, and weakness in the face of greater aggression by the demonic Fomóiri caused the chieftains of the Túatha de Dannan to rise up and cast him out. Bres, being half Fomóiri, fled to his father's kin and plotted vengeance against the Túatha de Dannan. In need of a king, the physician Dian Cécht built Nuada a new arm out of silver, allowing him to regain the kingship of the gods. Later, Dian Cécht's son Miach used draíocht to heal Nuada's arm and make it whole again, allowing him to lead the battle against the Fomóiri in the Godswar, where they were cast down at the second battle of Magh Tuiredh. Nuada's mortal form was slain in that battle, and his godly essence was unbound and released, returning to Tír na nÓg. As the rest of the Túatha de Dannan shed their bodies and rejoined him, he became the Árd Rí of the gods, ruling in Górias over the whole of the Gods. Nuada is the patron of rulers and warriors, being a god of kingship and the noblest of warrior virtues. He is seen as the epitome of what it is to be a rí or taoiseach, and is an exemplary role model for the laochra to follow. Wielder of Freagarthach, "Answerer" or "Retaliator", the sword which never misses and strikes any foe down, Nuada is held highly as the paragon of noble warrior virtues. It is Nuada that Túath na Ciarraide holds as the patron of our túath, for ours is a martial family and one who hold the kingly virtues in great regard. We venerate him highly as a result. In no way is his worship complicated, for it is, like so many other things about our beliefs, pragmatic, pious, respectful, and from the heart. We make sacrifice to Nuada by praying in a frank and honest manner, as Nuada has little patience for sycophantic speech, either asking for a boon or thanking him for one, and then placing silver, weapons, or armor into a pool of still water. We also venerate Nuada with the Roé, or sparring match, as the Roé itself is a form of worship in its martial purity. The sword is sacred to Nuada, and the image of Freagarthach is the sacred symbol that honors our patron god. Lugh Another of the leaders of the Túatha de Dannan is Lugh Lámhfada, the Ildánach, or many-skilled. Lugh, like Bres, is half Dannan, and half Fomóiri. Lugh is the God of light, not the sun as is often assumed, but of light itself. It was for him that the Gáe Assail was crafted, for the Gods, existing as they do outside of space and time as we know it, knew he would be born and use it, and they shaped it out of the element which he was most connected to- light itself. Lugh is also a god of the harvest, and it is in his honor that our fall harvest festival of Lughnasadh is held. Before the Godswar between the Fomóiri and the Túatha de Dannan, one of the seers of the Fomóiri had predicted that Balor's grandson would slay him. It was thus that he shut his daughter Ethnea into a tower sealed with draíocht. Unlike most Fomóiri, Ethnea was beautiful, and drew the attention of Cian, son of Dian Cécht. Cian managed to slip into the tower and make love to Ethnea, and she gave birth to Lugh. Ethnea, knowing Lugh would be destroyed if Balor discovered him, was smuggled to the Fir Bolg, where a queen named Tailtiu fostered him as her own son and raised him. Blessed with draíocht from both races, he grew quickly in power and skills, becoming ildánach, which means master of all arts and crafts. When he first went to the palace of Nuada he was stopped at the door by the sentry who said only those with a skill may pass. Lugh said he was a wright, but he got the reply that they had one already and so Lugh named all his professions in turn: smith, champion, harper, poet, lorekeeper, seer, practitioner of draíocht most cunning, physician, cupbearer, craftsman in metal, only to be told they already had experts in these. Lugh then asked if there was any single god among the Túatha de Dannan who had the whole combination of skills, and finding none, the gods allowed him to enter. Lugh was the master strategist who planned the final battle of the Godswar at Magh Tuiredh, but was forbidden from engaging in the fight. If Nuada was to fall, Lugh would be king in his place, and it was a horrible thought to lose one so gifted. However, after the battle was joined, Lugh used his draíocht to slip from his bonds and leap into the fray. He quickly rallied the Dannan troops, and struck deep into the heart of the Fomóiri hosts. Finding himself facing Balor, his own grandfather, he hurled the Gáe Assail and put Balor's eye out the back of his head, turning its baleful killing gaze onto his own men, slaying most of the Fomóiri hosts and ending the war. The remaining Fomóiri who had waged the war were captured and locked away in an Otherworld prison in a realm where they could no longer ravage Mide and the young races the Túatha de Dannan were teaching. Lugh remained in the mortal world longer than most of the Túatha de Dannan, though after the emergence of Man he remained more or less hidden. He fathered the great Ulaid hero Cúchulainn, and fathered the master musician Cnu Deireoil who served Fionn Mac Cumhail. He was one of the Dannans who remained in Éireann when men first arrived, and taught them the ways of the Gods. Lugh eventually faded from the mortal realm and returned to Tír na nÓg, shedding his mortal form and rejoining his father's kin. Today, Lugh is one of the most important gods of the Túatha de Dannan. He is revered as a god of craftsmen, warriors, lovers, poets, seers, and farmers. His light illuminates the world and drives back the darkness, and his courage inspires all. He is most highly venerated during the sacred festival that bears his name in August- Lughnasadh. We make sacrifice to Lugh by placing morning-cut holly or mistletoe, or silver, upon an altar while making prayers to him, then cast the items into water. His sacred holy day is Lughnasadh, the festival of Marriage and crafts celebrated between the summer solstice and autumn equinox. The spear is sacred to Lugh, and the image of the Gáe Assail is his symbol. Danú Though not a great warrior or king, Danú, also known as Dannan, is one of the most important gods of the Túatha de Dannan. Danú is the mother-figure of the Túatha de Dannan and, among other aspects, she is also the goddess of motherhood. It was her name that the Tribe of the Gods took as their identity, and it is she who we worship as our tribal matron to this very day. She is a sacred sovereign-goddess of Ireland, as well as being the goddess of home, hearth, and protection. Danú was the goddess who chose to lead the Túatha de Dannan from Tír na nÓg to Mide, and it was she who chose to shape those mortals in the lands she felt most a part of to follow the ways of the Gods. Unfortunately, much of the lore surrounding Danú has been lost due to the biased tendency of the early Christian monks to ignore all but the most outstanding tales of goddesses in Ireland. Though a decent amount survives, a great deal was lost along the way. What we of the Ciarraide know of her today that is not passed down in the lore is from our own hearts and instincts. To the modern Ciarraide, she is the protector of our sacred places and imparts great power to those who visit them. Being the goddess of motherhood, she is a patron to midwives and mothers, and often there is a shrine to her honor in birthing rooms, nurseries, etc. Danú is often thought of by us as the eternal mother in another way: she always tries to keep her children safe from harm. She guards us in our sleep, aids us in battle, and grants sanctity and security to the home. As most Irish will say "God bless all here" when entering a home, so too do we say "Danú bless all here" when doing likewise. We hold that the sacred times of Danu are the night of the full moon, sunrises, marriages, and any moment of familial bliss or power such as births. She is the protector of our sacred places and imparts great power to those who visit them, and she is a patron to midwives and mothers. We honor her with a shrine in nurseries where our children sleep, protecting them and watching over them. We make sacrifice to Danu by asking for her blessing, or thank her for some blessing given, and place items of beauty or representing family upon the shrine dedicated to her, or into a river. Eochaid Ollathair, �an Dagda�� b<<If Danú is the mother goddess of the Túatha de Dannan, then Eochaid Ollathair is certainly the father figure. Eochaid Ollathair, All Father, is a great and larger-than-life god who is the epitome of masculinity. Also called Ruadh Rofhessa, the Red One of Knowledge, he is a wise and boisterous god, enjoying feasting, fighting, acts of strength, harping, chasing women, mortal and divine, and many other pursuits. Eochaid Ollathair is called an Dagda, "the Good God", because he protects our crops, is the patron of feasts and feasthalls, and is generally a good and jovial god. The great cauldron Undrí, which supplies unlimited food and from which no company, no matter how great, ever walks away unsatisfied, was brought from Finias with him when he took on mortal form and came to Mide. Eochaid Ollathair carries with him a great club, nicknamed "Bod Mór" in honor of his proclivities for carnal pursuits, which was so great that when it was dragged behind him it left a track as deep as the boundary ditch between two provinces. This club could kill with one end and revive the dead with the other. His other great treasure is Uaithne, a living oak harp with which Eochaid Ollathair causes the seasons to change in their proper order. Uaithne also plays three types of perfect music, the music of perfect sorrow, the music of perfect joy and the music of profound and prophetic dreaming. Eochaid Ollathair is renowned for his appetites, both for food and for women. An example of his taste for food is found in the legends of the Godswar, the ancient conflict between the Túatha de Dannan and the Fomóiri. When the Fomóiri invaded Éireann during the Godswar, Eochaid Ollathair went to spy on them, and to try and delay them until the rest of the Túatha de Dannan were rallied and ready to fight. Eochaid Ollathair went to their camp and asked for a truce, which was granted, but to mock him the Fomóiri made him a porridge, because his fondness for porridge was well known. They made a great affair of it, filling every cauldron they had with milk, and then adding in a hundred whole sheep, a hundred whole pigs, and a hundred whole goats. The Fomóiri boiled it all and poured it into an enormous hole in the ground. Eochaid Ollathair was then told that he would be slain if he refused the Fomóiri "hospitality" and did not eat the entire meal. They underestimated Eochaid Ollathair, however, for he happily took his ladle, big enough for a man and a woman to lie in it side by side, and ate the entire thing. Eochaid Ollathair's appetites for women are likewise great, so great in fact that he stopped time to engage in a tryst. He had taken a shine to the goddess Bóann, wife of Elcmar, and she likewise returned his favors. So, while Elcmar was off on a day-long errand, Eochaid Ollathair slipped into his home and whisked Bóann off to a river valley, where he stopped time outside of the valley. The tryst lasted quite a while, and Bóann ended up pregnant as a result. Thus, Eochaid Ollathair had to keep time stopped for nine months so that she could give birth and return to her home with Elcmar none the wiser. Thus did Eochaid Ollathair sire Oengus Óg, named "Oengus the Young" because he was, as far as the outside world is concerned, conceived and born on the same day. A god of feasting, time, harping, masculinity, fighting, and the governance of the farming Gael, Eochaid Ollathair is a popular god among the Gael, and it is little wonder that �an Dagda�� is one of the more popular gods of our people. We make sacrifice to an Dagda before a feast, asking his blessing and placing food and drink upon the family altar, or a table set aside in his honor. The images of the harp and cauldron are sacred to an Dagda, and it is Uaithne the Harp and Undrí the Cauldron that we use as symbols to honor him. Brighíd Wisdom and grace are also virtues held highly by our people, and these are embodied in the perfection that is our most famous and broadly revered goddess, Brighíd. So important was she to our ancestors, that the Christians had to keep her around in the guise of "St. Brigit" to capitalize on the undying veneration she received, even into the Christian era. She is the goddess of wisdom, poetic inspiration, fire, and fertility. It is Brighíd who breathes life into the fires of hearth and forge, and passion into the mind of the poet and the musician. Brighíd is also one of the many gods and goddesses to whom we look for the protection and prosperity of our livestock and crops. It is she to whom we turn for protection of our animals, as a prayer of the Gael states- "I say the blessing of Brighíd That she placed about her calf and her cows, About her horses and her goats, About her sheep and her lambs. Each day and night, In cold and heat; Each day and night, In light and darkness: Keep them from marsh, Keep them from rocks, Keep them from pits. Keep them from banks; Keep them from harm, Keep them from jealousy, Keep them from draíocht, From North to South; Keep them from poison, From East and West, Keep them from envy, And from all harmful intentions." It is said that Brighíd�s name comes from the term Breo-Saighit, Fiery Arrow, for they say that when Brighíd crafted her mortal body, her essence was so great that a tower of flame reached from the top of her head to the heavens. Daughter of Eochaid Ollathair and Danú, she was among the highest ranking of the Túatha de Dannan. Thus, it was only fitting that she marry Bres the Beautiful, for this was before his cruel nature was fully revealed. She bore him a son, Ruadan, who chose to leave with his father when Bres was finally overthrown. Later, during the Godswar, Ruadan was sent by Bres to spy on Goibhniu the smith god. Goibhniu was busy making magical spears out of the very essence of the world, powerful and sleek weapons designed to kill the Fomóiri. Ruadan grabbed one and stabbed Goibhniu with it, but the smith god is made of tougher stuff than such that would die from his own weapons. He pulled the spear out and cast it at Ruadan who, being partly of Fomóiri blood, was struck dead. Brighíd saw this, and gave out a cry of grief, a caoin or "keen" as it is known, to lament the loss of her son. Thus it is our most sacred Brighíd who started the tradition used by our people at funerals to this day.

Though the veneration of Brighíd is shared by Christian and Sinnsearaithe alike, as are holy sites to her such as her holy well in County Cavon, Éire, she is one of the most highly regarded goddesses of the Sinnsearaithe. It is in her honor that we celebrate the coming of spring with the great festival of Imbolc in the beginning of February. February hardly seems like the beginning of spring on the surface, but the signs of the coming season begin appearing around this time. Hard storms lessen, new grass begins to grow, sheep give birth, and farmers ready their gear to plant the first seeds of the year's crops. Brighíd is the goddess who breathes this new life into the world, just as she does into a woman's womb. In this way, the gift of fertility to our people, animals, and land, Brighíd is one of the core deities of our very existence. Without her, there would be no life, only the harsh and cold grasp of winter. We make sacrifice to Brighíd by finding a place of natural beauty near water and, making prayers to her, cast jewelry or similar items into the water, or by tying "prayer rags"- strips of cloth with prayers on them or said as they are tied- to trees above the water. The Brighíd�s Wheel, a type of three-armed cross often made of woven reeds, is a sacred charm of protection blessed by her. In addition to these gods of the Túatha de Dannan, there are many whom we call upon for certain occasions, or who govern certain aspects of life as we know it. These gods are not lesser deities, per se, simply not venerated on a daily basis the way the above gods are because of their auspices being more focused. Áine Áine the Beautiful, whose name means "delight", is our goddess of safe passage and protection on voyages, for she can be asked to gain her father's favor for those who cross over his realm. She is also known for her gifts of healing, and is the very essence of life and vitality. Among the liaga (physicians) and midacha (healers), Áine is said to be the one who creates the spark of life, the binding spiritual "glue" as it were that keeps the soul in the body. As with Brighíd, she is venerated by women for her gifts of fertility, mainly by giving a woman a healthy body and child. It is likewise that she is seen as providing prosperity for our people, as strong children and good health are the greatest treasures a Gael can have. Áine is one of the longest-revered goddesses of the Gael, having been revered well into the 19th century by a festival on the hills of Cnoc Áine, where folks would dance with torches around the stones there anti-clockwise. They then sprinkled the ashes of the torches on their fields and livestock in order to grant them fertility and health. Áine is the daughter of Manannan Mac Lír and Fand, and is sister to Grian, the goddess of the sun. When the Túatha de Dannan came to Mide, they took primitive men and shaped them into their followers by teaching them how to work metals and build, and how to sing and make music. Over the millenia, the Túatha de Dannan took various families under their wing, sometimes even siring half-gods among them. Such was the case with Áine, for she gave birth to the founder of the Eoghanacht line, and guided them well after most of the Túatha de Dannan had returned to Tír na nÓg. She led them to settle in the lands she held dear in what is today Knockainy, where they settled under her protection. In fact, it was while still in mortal form and watching over her children that Ailill Olum, a king of Munster, learned the hard way what happens to those who harm Áine or her children. One Samhain, Ailill Olom and Ferches, a draoi who also knew the arts of war, went to graze his cattle on the hill of Knockainy (Áine's hill) without permission. Áine used draíocht to cause all grass to disappear from the hill, denying Ailill his ill-gotten gains. Ferches and Ailill attacked the Eoganach when they saw them, and their chief, who was Áine's kin, was slain. In his arrogance, Ailill captured Áine and tried to rape her, but Áine managed to bite off his ear in the struggle. Afterwards, Áine swore a curse of revenge on Ailill saying: "Ill have you been to me, to have done me violence and to have killed my father. To requite this I too will do thee violence and by the time we two shall have done with one another I will leave thee wanting all means of reprisal." And this was no idle boast. Áine caused the land to rebel against Ailill, as is the fate of an unrighteous king, and brought about the ruin and death of Ailill and his seven sons. Thus did she avenge those who had wronged her chosen kin, and show the justice that would be dealt to an unjust king. Áine soon left the mortal world and it's vulnerabilities behind after this, but still looks in on her people and protects them from time to time. It is said that she appeared on her hill during the Famine in the 19th century, handing out food to her people. In honor of her protection and the gifts she gives us, the three days following Lughnasadh are sacred to her, and in that time no blood may be shed in anger, for such is supposed to be a time of peace in her honor, or for surgery, for to do so would cause the life spark to escape and the soul to leave the body. Anand "an Mórríghan" Anand, or an Mórríghan- "the Great Queen"- is probably one of the most enigmatic deities we honor. She represents so many brutal and harsh aspects of our lives, mainly war and vengeance, that she would seem to be a deity which one should fear and avoid, yet she is also prone to granting great favor in battle, and is highly respected among our people. She is one of the goddesses of war, and she is a masterful paragon of warrior-ways, but unlike Nuada, who represents the almost chivalrous and glorious aspects of warrior-tradition, an Mórríghan embraces the harsher side of war. She is the punisher of cowards, who strikes down those who would flee the battlefield, and she is also the giver of the riastarthe, the warp-frenzy made famous by Cúchulainn. An Mórríghan is also the goddess of vengeance, especially through the use of poetic justice. This was sparked long ago, when humanity was still young and the Túatha de Dannan already ancient beyond imagining. An Mórríghan had given birth to a son named Mechi, who was mortal but had three heads and three hearts. Due to his deformities, mortals led by Mac Cecht, son of Oghma, slew Mechi, and an Mórríghan, in her grief and anger, swore revenge against all mortals by cursing them with ingenuity, especially when it came to killing weapons. Thus, her vengeance would be that humanity would one day destroy itself with its own weapons. It is said that she has since forgiven mankind, seeing as we have managed to avoid wiping ourselves out, but there is little doubt that she will not step in to stop humanity from engaging in self-destruction. An Mórríghan is not an entirely vicious deity, though the above may seem to indicate that. She is more than just a blood-drenched goddess of battlefield savagery, for she is also the goddess of prophecy and draíocht. All among our people who would seek to have visions must honor her, for it is she who has the Sight and governs its use by mortals. She has made many prophecies and seen many things, but the one prophecy she made that haunts our people to this day is that which was made of the times we may very well be living in now- "After the battle was won at Magh Turaidh, and the slaughter had been cleaned away, the Mórríghan, goddess of war and prophecy, proceeded to announce the battle and the great victory which had occurred there to the royal heights of Ireland and to its hosts, to its chief waters and to its river-mouths. And that is the reason the Morrigan still relates great deeds. 'Have you any news?' everyone asked her then. 'I do, a foretelling of time to come. The lay of the great cycle of years.' 'Tell us what portents you see for the world to come.' they asked. The Mórríghan used her draíocht and her gift of prophecy to proclaim the height of the cycle. 'Peace to as high as the sky sky to the earth earth beneath sky strength in everyone a cup very full a fullness of honey honor enough summer in winter spear supported by shield shields supported by forts forts fierce eager for battle fleece from sheep woods grown with antler-tips (full of stags) forever destructions have departed mast (nuts) on trees a branch drooping-down drooping from growth wealth for a son a son very learned neck of bull in yoke a bull from a song knots in woods wood for a fire fire as wanted palisades new and bright salmon their victory the Bóinn their hostel hostel with an excellence of size new growth after spring in autumn horses increase the land held secure land recounted with excellence of word Be might to the eternal much excellent woods peace to as high as the sky be this nine times eternal' 'Then greatness is to come!' everyone shouted as they rejoiced. The Mórríghan silenced them, for she was not yet finished with her words. She then prophesied the end of the cycle, foretelling every evil that would occur then, and every disease and every vengeance that would befall the world as one cycle died and a new one was born. She chanted the following poem: 'I shall not see a world Which will be dear to me; Summer without blossoms, Cattle will be without milk, Women without modesty, Men without valor. Conquests without a king Armies with no nation Woods without mast. Sea without produce Fields without bounty. False judgments of old men. False precedents of lawyers, Every man a betrayer. Every son a reaver. The child will go to the bed of the parent, The parent will go to the bed of the child. Each their siblings mate. They will not seek any mate outside his house And twisted will be the forms of their offspring. An evil time, Son will deceive his father, Daughter will deceive mother, Husband deceive wife, And children and elders will be cast aside.' 'A dark time indeed!� everyone cried. This foretells the cycle of years, which is ever-eternal. These times are reminders that one begets the other, the times of evil are the death of the old world and the birth pangs of the new. The greatness of the height of the cycle is a time to prepare for the end of it, lest you be caught unawares and perish.�� Prophecy is not the only draíocht art an Mórríghan teaches, for she is also a master of the long-lost art of shape-changing. Many forms does an Mórríghan take, both in our tales and today. Cúchulainn encountered an Mórríghan in a variety of forms- a woman with long red hair, red eyebrows, wearing a long red cloak and carrying a gray spear riding in a chariot, a heifer, an eel, a wolf, and as an old crone. She is most often seen as a large, glistening black raven, which is her symbol. An Mórríghan is also a goddess of death. Though this could be inferred from the fact that she specializes in dealing death out to people, she governs another, gentler side of dying. An Mórríghan often appears to warriors on the day of their death as a bean-nighe, or washer-woman, where she will be seen washing the armor or uniform of the soldier who is to die. This may seem grim, but it lets the warrior know that his day has come, and inspires him to live his last day with glory and honor. After he is slain, an Mórríghan then guides him through the Imrama nAnam, the Soul Journey, whereon he will be taken to rejoin his ancestors in Tír na nÓg. She is a guide to the slain, especially warriors, and she ensures they reach the afterlife safely. For this reason, and because she gives us strength in battle and grants our draoithe their gift, an Mórríghan is venerated on those occasions. We make sacrifice to her with caution, though in much the same fashion as Nuada, for she is often demanding in her favors. Sinnsearaithe venerate her at times of battle, when one needs vengeance to right a wrong, or at Samhain, when her prophetic nature is sought. The raven is sacred to Mórríghan , and is often her messenger. Sinnsearaithe pay head when three ravens croak at once, for we believe they are her voice and often give portents of doom or preceding great strife or war. Goibhniu God of blacksmithing and brewing, Goibhniu is said to brew a mead that tastes like condensed pleasure, and is the brewer of the Gods' wine and ale. He is the master weaponsmith of the gods, and has no equal in the forge, mortal or otherwise. Three blows of Goibhniu's hammer make either a spear or sword without equal, able to strike down the enemies of the Gods without error. Goibhniu is a builder, a chef, and a doting father. It is he who overseas machinery, computers, weapons, and those who build them. We see him in the fires of the forge and the glowing iron being shaped: hear his voice in the ringing of the smith's hammer. Blacksmiths within Sinnsreachd consecrate their forges to him by placing tools of their trade upon an altar in a workshop to consecrate that shop or forge, which is then left undisturbed for the life of the sacrificer or the use of the building, whichever ends first. Said smiths further honor Goibhniu by marking his symbol- the hammer, anvil, and tankard- upon items crafted in their forges. The Gabha Uirlisí- the Hammer, Tongs and Apron- are sacred to Goibhniu, as is the Altóir Inneoin, or Anvil Altar, and are symbols of his might and blessing. Macha Goddess of horses, war, sovereignty, and the sacral bond between a rí and the land. Macha is best known for having taken mortal form to become the wife of Chrundchu mac Andomain, an Ulster landowner. Chrundchu was a widower, and Macha came to him one day, and began to live as his wife. They got on well, and Chrundchu lived in bliss for a time. One day, Chrundchu went to the court of Conchobar, king of Ulster, and there boasted that his immortal wife could outrun the fastest horse in Conchobar's stable. Conchobar called for her to be brought to the court to prove this assertion. She was heavy with child at this time, in the last stage of pregnancy, however. She asked to be allowed to return home, but Conchobar insisted that she race his horses to prove what her husband had said, on pain of her husband being killed if she refused. She called three times to the crowd of people to relent, each time in the name of the mothers who bore them, but the crowd also refused. So, she raced Conchobar�s horses and won. At the end of the race, she squatted before the gates of Conchobars palace and gave birth to twins, two immortal children said to be able to turn into horses of perfect form. As she gave birth, she cursed the men of Ulster that they would suffer for nine days in the pangs of labor in the time of their greatest need. Conchobars palace and the surrounding village was renamed Emain Macha- The Twins of Macha- from this event. Macha is a Goddess of sovereignty, as well as motherhood, and horses. Along with her sisters An Mórríghan and Badb, she is also a goddess of war, and is the third raven heard when An Mórríghan speaks. It is Macha who gives legitimate power to the rí by binding his rule to the land, thereby ensuring that the people prosper or suffer based on their choice of a chieftain. Needless to say, this encourages them to choose wisely. Macha advises ríthe as to the proper way in which they should rule, and will judge a rí worthy or unworthy and the land will bloom or rebel accordingly. She is a patron of the family, and will always protect families alongside Danu. Macha is master of the end and rebirth of the cycle, a period best attributed to winter. Due to this, she is often seen as an old woman in many tales, but is just as likely as her sisters to appear as a young woman or a horse. Macha is venerated in similar fashions to both her sisters and Danu, and is most often venerated during winter. The horse is sacred to Macha and a symbol of her power, especially twin horses.Oghma The god of knowledge, warrior-poet natures, and eloquence, it is Oghma who presides over learning and writing, and the first Gaelic alphabet, Ogham, was named in his honor. Oghma is also the god of writing, runes, draíocht, wrestling, war and wisdom. He empowers runes with his magic, and now that we are a literate people, he is the patron of the written word. He is the father of wisdom and the wise. Oghma is the best wrestler of the gods, and is venerated by hand to hand combatants and the laochra. Those dedicated to oghma's teachings learn the art of wrestling well- be it traditional arts or those from other lands and of modern origin- and His name is sacred within our halls of training and our schools. Sinnsearaithe honor him through the dedication of great works of literature or knowledge, and inscribe his name in his language throughout those places and works of knowledge, learning, and wrestling where he is venerated.Manannan Mac Lír The Waverider, son of Lír, Manannan is the god of the seas and guardian of the gateways between this world and the otherworlds. Manannan is venerated most of all as the Opener of the Way, the traveling deity who you should ask to guide prayer and invocations to the other Gods, and for guidance when seeking to speak with the other realms. Manannan is also the guide to the Otherworld, at least of living visitors, and those who died at sea. He is the ruler of all oceans and the keeper of their secrets. Manannan is the patron of sailors, fishermen, and any who desire a safe voyage. We are always wary of his wrath, however, for his temperament is akin to Cromm Cruach's. He is the sinker of ships and the giver of life to those who fish in his domain, and is venerated by them. He is the crashing of waves against the hull of a ship, the raging waves of a storm that drown ships, and the ruler of Tír Tairngire, the realm beneath the waves. We make sacrifice to Manannan by casting silver, hand-forged iron fish, or spears into the ocean while asking for a safe voyage. Manannan's sacred symbol is a special form of triskellion, with feet at the bottom of the three legs, enclosed in a circle, that has become the symbol of the island nation named for him- Mannan.Badb Catha The last of our Gods to be seen in physical form, at least until recently, Badb is the bringer of victory, a battle-Goddess and sister to An Mórríghan. In fact, Badb is the second raven of the three seen when An Mórríghan speaks. She is the goddess of fury and victory in battle, and governs the sovereignty of warrior-kings and queens. It is Badb to whom warriors pray to gain victory, and she rewards the brave and righteous with such. Badb last made a recorded appearance in 1318 CE before the Battle of Dysert O'Dea, where she granted Clan Turlough victory, after which they honored her in their writings- Caithréim Thoirdhealbhaigh, or The Triumphs of Turlough- as "a war-goddess woman-friend". She was also seen before the famous Battle of Clontarf in 1014 CE, in which she danced above the points of the spears of the Irish warriors and granted them victory over the Northmen mercenaries of a rebel king. Badb is a goddess who brings victory in war, but we are cautious in our veneration, for she also starts them. She stirs up conflict that it may be won by the brave and the righteous, a contest of skills to prove the worth of warriors fighting it. It has often been said that she creates wars to weed out weak men and women, and allow the strong to prove themselves. Badb Catha is called on for victory in war and fighting, or for excellent combat skills, but we are wary of calling her for anything else for, like her sisters, she has a temper.Dian Cécht Honored for his healing arts, Dian Cécht is the Physician of the Gods. Dian Cécht is the one who, after Nuada lost his hand in battle, crafted a silver hand of beauty and skill, with the same strength, mobility, and sense of touch as his original. Dian Cécht has a dark side, however, like many of our Gods. He once had a son, Miach, who grew to become more talented than he at the art of healing, using herbs and draíocht instead of artificing and surgery. After Nuada's lost arm had been replaced by a silver one, Miach made it whole again, flesh and blood, where Dian Cécht had been unable to. At that time, the gods were young, and prone to make terrible mistakes in their youth. Diancecht slew his own son out of jealousy and scattered the herbs his son had used to effect his healing arts so that noone- mortal or God- would ever be able to use them again. He came to reason in time, however, and was so horrified at the act that he swore he would spend the rest of eternity helping others by aiding them, helping mortals rediscover the herbs and medicines over time and teaching them the art of healing. Thus, out of a horrific act of fingal came the god who taught our people to heal. Dian Cécht has taken up his son's mantle, and is the patron of herbalists for he is the one who gifts them with his secret knowledge of what plants heal, and how to use them. He is the patron of physicians and surgeons, for his original purpose is still held and honored. Sinnsearaithe call upon Dian Cécht when in need healing or when we need to heal another. Dian Cécht is embodied in the edifice of places of healing, and in the touch of a gifted surgeon. We make sacrifice to Diancecht by burning healing herbs, either on an altar in the home, or at the hospital where someone is in need of healing (though this is increasingly difficult these days due to hospital regulations). The ash staff is sacred to Dian Cécht and is carried by the lia and other healers.Cromm Cruach The Old Man of the Hill, the Lord of the Skies Above, Cromm is the god of the hills, mountains, weather, storms, and space. Quick to anger, his demeanor is reflected in the skies above, the rumblings of the mountains, and the stubborness of the earth in its unyielding battle against the elements. His moods are as ever-changing as the weather he controls. Cromm is the god of the hills, the everlasting sky, and all that dwells above it. It is he who clutches the stars to his bussom and strikes down the foolish with flood or drought. We all walk under his sky or amidst his ebony home where he places the stars to guide us, and we must be wary lest we raise his ire. We make sacrifice to Cromm by placing a libation of wheat, corn, iron, or precious herbs on an altar under the open sky while making prayers to him. Mountains and hills are sacred places for Cromm, and shrines in his honor are best placed atop one.Having come to know our gods, who and what they are from our viewpoint, it now becomes important to understand our view of the universe in which we all exist. The cosmology of the modern Sinnsreachd Gael is very different from that of our ancestors thousands of years ago. As our scientific understanding of the universe has evolved, as well as our general understanding of the broader sense of celestial interactions, our primitive animistic views of the universe have expanded and adapted. Likewise, our understanding of the scope of existence has expanded and our cosmology has followed suit to embrace the idea of other worlds, galaxies, and our place in this huge stage upon which life is played out. To further delve into this, we move on to the second major question. What is the nature of the universe? The dictionary defines a universe as "the whole body of things and phenomena observed or postulated; the world of human experience." This definition is a nice, tidy, surgical definition of the realm of existence about us, but it does little to explain what it is. Each culture and religion is thus charged by its adherents to further expand upon this unostentatious cosmological exposition through their own filters of mythology and folklore. The Gael, ancient and modern, have done so through the cultural, religious, and empirical paradigms in which they have existed throughout history. The universe as we see it is many things, but to start with the general concept, it is the plane of existence that we can see, feel, and study that surrounds us. In this regard, we are in agreement with and have not really expanded beyond the scope of the dictionary definition, and it is here that we begin honing the cosmological paradigm into specific aspects. The universe as a whole is a macrocosmic parallel of what we experience here on earth, and the entirety of existence- all of the universes and levels of reality- are likewise a macrocosmic parallel of our universe. In other words, what we see around us in our own lives is but a smaller version of the grand mechanism that is the universe. We love, laugh, hate, cry, build, plan, play, and fight. Likewise do the Gods and spirits of this universe and every other. The world is neither fair nor balanced, but seems to have its own symmetry, a form of imperceptible self-regulation that keeps it in check from going too far towards chaos and anarchy, or too far towards restrictive order and systematization. So too is the broader universe organized in a self-regulatory fashion. In spiritual terms, Mide- the physical universe in which we dwell- is the realm in which we are meant to spend time experiencing mortality in order to both experience life and all that it has to offer, and to further advance and evolve our souls. To the Sinnsreachd Gael, the universe is neither inherently good nor inherently evil, it is both simultaneously. The universe is, in a way, a living entity, though not sentient, and as such it is a fluid and dynamic entity wherein acts and entities both good and evil occur constantly. There is not a �balance�� between good and evil in the universe, because the actions of entities, mortal, immortal, and divine, affect it dramatically. Much as we view the natural world around us as inherently amoral, prone to acts of brutal savagery or gentle beauty seemingly at a whim, so too is the universe neutral in respects to morality. Not being sentient, it is incapable of such things. However, the uncountable teeming multitudes of entities, especially the gods and spirits, affect it according to their own whims and desires, thus taking the universe from a neutral existence and turning it into something akin to the Cold War world many of us were raised in. We believe that the Gods use Mide, the physical universe, as the forge in which they shape their creations, us, and the battlefield upon which they fight against those of opposing ideologies. Many tribes of gods and individual kinless gods have agendas that conflict with one another. Existing outside of this universe, or the general concept of time and space as we know it, they do not deal with each other directly, but instead act through proxies in the realms of physicality. Those proxies would be the mortals and immortals who dwell in those realms. In short, the tribes and nations of man and spirits of the world choose sides in a conflict that spans the multiple aspects of existence itself- chess pieces on an unimaginably complex board in which a nearly infinite number of players move an even larger number of pieces in their contests with one another. Some find the idea of the universe being driven by the dynamics of a multifaceted conflict between numerous deities and entities frightening, but we find it comforting. Knowing that these conflicts give life and vitality to the universe, the Gael, who live by a warrior-poet ethic and a heroic morality to begin with, find themselves in a comfortable niche as followers of one of the more dynamic, if sometimes aloof, tribes of gods. Where others seek to abscond from this world, following religions and philosophies that teach escapism either through esoteric spiritualism, naïve utopian idealism, unattainable concepts of �enlightenment��, or a fanatical obsession with the afterlife at the expense of the mortal life, the Sinnsreachd Gael embraces Mide fully. The universe is our home, where we were placed for a reason, and we would be remiss in our obligations to our Gods and ourselves if we did not live life to its fullest. Our view of our place in this universe is that, while we are here to do the will of our Gods and Ancestors, we should also experience life fully, seeking challenges and rejoicing in the triumphs we make. While we understand that we are immortal souls in mortal shells, those mortal shells are a part of us. We believe one should embrace physicality and spirituality, rather than chose one or the other. The Sinnsearaí rejoices in life and lives it to the fullest. We are not ashamed of physicality, either the universe itself or simply our bodies, nor do we feel that it is evil. Actions, thoughts, and motives are evil, but the raw physical world that is Mide is not. With the nature of the universe and our place in it explained, we must begin to focus in closer to home. Thus, we move on from cosmology to anthropology, not as a science, but as a theological concept. This brings us to our next question. What is the nature of Man? Mide is populated by many peoples, those we know who share this world with us, and those who may dwell out there among the stars. Working with what we know, humanity by itself is a very diverse and complex species, and thus there is no single answer to this question from a scientific point of view. However, from the Sinnsreachd perspective, there shouldn�t be one. As has been explained previously, we see humanity in its intended state as being divided up into tribal groups. Each tribal group has a set way of living, language, and beliefs given to them by their respective gods as the way in which they were intended to live. Thus, each of these tribal groups must be viewed individually rather than as some mythical collective cultural whole. The nature of the Sinnsreachd Gael as a people, in our intended state as given to us by the Gods when they taught us, is that of a spiritual yet practical people whose lives and paradigms are centered around the family and túath. Individually, we are made up of three elements- Corp (Body), Spiorad (Spirit), and Anam (Soul). The body is the physical shell that is made to house the fragment of our souls that we send to experience mortal life. It is, in many ways, the house in which we dwell for a time. The spirit is the animistic spiritual element that binds the soul to the body and teaches it how to exist in physicality. Souls are immortal entities that do not necessarily have a full comprehension of how to exist in mortal form. Things such as eating, breathing, making the heart beat, moving the arm while staying in the body rather than sending the soul out of the body to move something, etc. are all the job of the spirit. The soul is the immortal essence that is our thoughts, beliefs, memories, emotions, etc. Our souls, it is believed, were created by the Gods when humanity didn�t even exist as we know it; crafted from a piece of their own essence. Primitive creatures were slowly shaped by the Gods and our infant souls placed in them to begin learning. Over time, the experiences of the mortal world and the teachings of our gods in their realm where our souls dwell when we die began to mature them, giving us wisdom and higher thought. Our souls were sent back into new bodies after a brief time in Tír na nÓg, and over time we began to understand things differently. A higher level of consciousness emerged, first in tool-making, then art, then music, and so on, a process that continues to this day. What the end goal is, no one can say. Some believe the Gods are shaping our immortal souls to one day be like them, gods of some other realms. Others believe that we are meant to remain here always, expanding our knowledge and wisdom while always being connected to mortal forms. Only time will tell, and in the meantime, we live, die, enjoy a century or three of bliss in Tír na nÓg, then are reborn and start it all over again. Understanding the nature of man, and of the Gael as we were intended to be, one is forced to wonder what causes some to stray from the teachings of our gods, and what happens to them. The question of sin and salvation, in a way, is what we have come to next. What are the right and wrong ways for living? Soteriology is the theological study of salvation, mainly from the Christian perspective, but it can be applied in general. The principles of the study of a religion�s �salvation�� principles basically break down to the concepts of Proper Living, Sin, and Judgment. While many reading this will undoubtedly balk at the idea of a Christian-based theological science being used to review the concepts of right and wrong held by a distinctly non-Christian culture, these three basic concepts are surprisingly universal. Thus, it is through these three concepts that we shall explore Sinnsreachd notions of right and wrong. A character in a famous movie from the early 80�s asked �What is best in life?�, and received an answer befitting the ravaging rapacious hordes that our ancestors are believed to have been by some. If you asked this of a Sinnsearaí, she would tell you that the best things for a Gael are to live a life in which honor, courage, integrity, valor, and piety were the chief ethics. A proper life, she would continue, would involve being close to and caring for one�s family, being prosperous, prolific with children, striving for greatness, and living by the ethics taught to us by our ancestors. Proper living for the Sinnsearaithe involves service to one's family, namely by remaining dutiful to the túath and serving the people with honor. Proper living is not hard- basically love and honor your family and túath, act with honor and courage, wisdom and dignity, and keep the core ethics of the Sinnsearaithe close to your heart. There are some, however, who are incapable of or choose not to follow these ways. This is where we find people who live wrongly. Though we do not have the same concept of �sin� as the Christians do, we do have ethical breaches and outright condemnable behavior that is our equivalent thereof. Acting with dishonor, cowardice, immorality, impiety, and so on are obvious breaches of the religious ethics of our people, but there are more specific examples that will help people understand what we mean by these broad generalities. Shaming one�s family, túath, or the Gaelic people as a whole through actions such as crudeness, public intoxication, laziness, slovenly behavior, lewd acts, etc. is not only condemned by secular ethics, but by our religious morals as well. An example- �Trí comartha clúanaigi: búaidriud scél, cluiche tenn, abucht co n-imdergad. Three ungentlemanly things: interrupting stories, a mischievous game, jesting so as to raise a blush��. �Trí hingena berta miscais do míthocod: labra, lesca, anidna. Three maidens that bring hatred upon misfortune: talking (excessively), laziness, insincerity�� Worse by far are severe wrong-doings that harm others, and as a result, harm our people as a whole. Some of these acts are crimes in almost every society- rape, murder, child abuse, etc.- but others are crimes and atrocious acts only among our own people. Things such as oath-breaking, betrayal, kin-slaying (which in our eyes is even worse than murder), and abandonment of children are horrible acts that violate our ethics. Other things, actions such as slandering, abuse of women, elders, or children, and the like are among the things that constitute living wrongly among the Sinnsreachd Gael. When someone commits these acts, they face the judgment of the túath, and when they die, they face the judgment of the Gods. If a person who has lived wrongly or done wrong deeds in their life has not atoned for them before he dies, then when an Mórríghan comes for his soul to take him along the Imrama nAnam, he will face her judgment. If found lacking, then he will not be taken to Tír na nÓg, but instead taken through Muir Ceo, the Sea of Mists, and dropped on an �island��, a metaphor for the many other worlds that exist along the Imrama, which is specifically shaped to deal with his particular wrongdoings. He will find himself suffering the fate he inflicted on others- if a rapist, he will be put in the body of a woman and be brutalized, if a thief, he will be made wealthy only to lose it all to thieves, if a coward, he will be forced to face a horrendous enemy and be abandoned by his allies, unable to flee himself. Eventually he will learn the error of his ways and be sent back to Mide to try again, and he will have to start from square one all over again. Those who are found to have lived well, and who have atoned for any misdeeds they may have committed, will be taken by an Mórríghan and pass through Muir Ceo along the Imrama nAnam until they reach Tír na nÓg. Once there, they will be judged by their ancestors and the Gods to see if they have completed the tasks which they were sent to Mide to complete. If so, they will have earned the right to stay in the Land of the Young with their ancestors and enjoy centuries of rejoicing and eternal feasting. If needed again, or if they chose (the afterlife being perfect, and perfection eventually getting boring), they will be sent down to a body, often (but not always) within their genetic line. Thus are we both bound for an afterlife and reincarnated as well. All of the ethics and cultural elements we have that are so important to a proper living come from our ancestors, and from our Gods. The methods and principles behind such impartation of knowledge are the basis of the next question we shall discuss. What is the nature of revelation and divine wisdom? The culture of the Sinnsreachd Gael as well as our ethics, morals, and even our social structure are held by the modern Sinnsearaithe to be given to us by the Gods as the proper way of living. The question often arises about how such transmission of information takes place, and it is here that we shall explore this issue. Coming from the standpoint of a religious faith rather than an archeological science, there will be what some may consider unempirical methods to our beliefs, but this is to be expected. If science and belief were 100% interchangeable, we wouldn�t need both, and thus we keep science to its own duties and faith where it belongs as well. However, there are some methods of the transmission of divine wisdom which are comfortably in the middle, being under the auspice of both. Canonical sources such as the many manuscripts that have survived the ages form a great deal of the core of the reclamation of our native culture, but they were also instrumental in the rebuilding of our beliefs. Many rites and rituals, tales of our gods and their lives, the Godswar, and so on were all preserved in these manuscripts. From the academic and scientific point of view, these manuscripts preserved enough information to create a skeletal frame on which to build the religion, fleshed out with extant folklore and customs still preserved in Ireland and in the Gaelic diaspora. The religious point of view is that these particular tales and books were preserved through divine intervention to ensure that they survived the 1,500 years of Christianity to reach those who would resurrect the worship of the Túatha de Dannan in the proper way. With the framework established by the information from the manuscripts, the fleshing-out came from the integration of existing tales, superstitions, folklore, rites, rituals, customs, and so on. Most of these were still virtually untouched by Christianity while some required moderate de-Christianization to bring them back to their polytheist origins. While it is impossible to rebuild the religion 100% as it was, nor is it possible to fully remove all traces of Christianity from them, enough of both was done to allow for a functioning, culturally-appropriate religious belief that is a direct, if non-linear, descendant of that which our ancestors followed. We believe that these customs and traditions survived because our Gods never abandoned us, our ancestors simply abandoned them. The Gods knew it was only a matter of time before the Gael began returning to their native beliefs, in one fashion or another, and thus ensured that the appropriate things were kept alive. There are methods through which the Gods and Ancestors impart information that are purely spiritual and religious, and cannot be governed by empirical measurements as they fall firmly into the auspice of faith. Chief among these are visions and dreams that are given to many of our people. These are differentiated from normal dreams by a series of key images or phrases that mark their validity from a Gaelic perspective, as well as prophecies that come true shortly afterwards as a confirmation of the vision. These help separate the visions from innocent dreams, but they also separate the visions of legitimate people gifted by the Gods or Ancestors from false visions of charlatans or the insane. Other methods through which the Gods and Ancestors impart information to us are divination and portents. Divination is done in many ways, each closely guarded by the draoi who uses them. Most generally center around achieving a trance-like state in which the draoi or fáidh (prophet) is able to see things from outside of the normal realm. Sometimes they are able to go on an Imrama and see things in distant places or even times, but more specifically to the matter at hand, they are able to contact the Ancestors, who pass information along from the Gods or from their own wisdom. the scientists call this �remote viewing��, but we avoid such surgical terms and ideas, for we know that there would be no vision if the Gods did not will it.

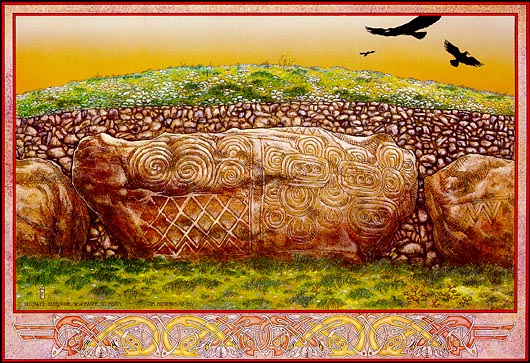

an Daoine Síoraí With the basic tenets of our beliefs explained, it is time to move beyond the mortal world and meet some of the immortal entities of the universe as we know it. The Túatha de Dannan have been discussed already, as they are the gods who are core to our beliefs, but there are many other beings who we deal with (voluntarily or involuntarily) that must be discussed. Known collectively as the Daoine Síoraí, or Eternal People, these beings are those who are between us and the Gods on the scale of power and existence. Spirits of the land, ancestral souls, demonic entities, and non-corporeal beings from the Otherworlds are the subject of this next part of Sinnsreachd belief. Chief among the Daoine Síoraí, and most famous among them, are the beings known as Daoine Sídhe. These powerful beings comprise a great many beings, some alien and nearly as powerful as the Gods, others very much connected to this world and little more than mischievous or helpful spirits. The Daoine Sídhe mostly come from various Otherworlds which are accessed through the draíocht of the mound-gates. These sacred hills are the physical markers of the boundaries between this world and theirs, and can be breached by both mortals and the Daoine Sídhe under the right conditions. Though their motives are unknown, the Daoine Sídhe visit Mide in cyclic waves; sometimes appearing in large numbers for several centuries, then go virtually unseen for a few more centuries, only to reemerge for another cycle. They seem to have specific times and types of places that call to them, though the pattern to such things is, in large part, a mystery to us. The Daoine Sídhe can take human or human-like form, but their minds and ways of thinking are very alien to us. They seem to be a blend of grand cosmic power with near-psychotic child-like emotional states, many of whom do not seem to understand the fragility of the mortal form. Morally, the Daoine Sídhe are neither good nor evil, but seem to have elements of both. Some lean more to one end of the spectrum, some to the other end, but most are in the center in a strange moral limbo in which their actions cannot be judged the same way we would judge other mortals. As many of the legends of our people tell, they will often play with us, inviting us to dance with them in their revels. Such festivities are usually fatal to mortals, however, and the Daoine Sídhe seem to either be unable to comprehend this, or simply do not care. Some of the species of Daoine Sídhe are well known to our legends, such as the Lúracán. Commonly known to deoraithe as �Leprechauns��, the Lúracán are cobbler spirits who make shoes and are fond of alcohol. Often, good folk will leave out offerings of whiskey or mead for them and find their shoes patched up in the morning. The Lúracán are some of the most benign of the Daoine Sídhe, being helpful to mankind. Others, like the shape changing Púca, are not so nice. Mischievous and often harmful, Púcaí are known for their trickery and cruel pranks. Púca will do such things as appear to be an object of value and, once picked up by an unwary traveler, slowly grow heavier and heavier until the traveler is overburdened. They also delight in taking the shape of pets and trying to gain entry into homes (Púcaí cannot cross a threshold unless invited, and they will trick people into inviting them by pretending to be a favorite pet). Once in the home, they unleash all sorts of mischief and mayhem. Another annoying species of the Daoine Sídhe are the Clúricán, relatives of the Lúracán. These are basically the antithesis of the Lúracán, being lazy, as they abhor physical labors, and prone to stealing food and drink in the middle of the night. More of a nuisance and relatively harmless, it is said that those who give ill treatment to the Lúracán will be visited by these nasty buggers as punishment. Another famous type of Daoine Sídhe is the Síofra, otherwise known as a Changeling. These creatures, also known as Malartán, are switched out for human children, which are stolen to replace the sickly Síofra. These creatures are not very dangerous, but their appearance comes in the wake of a child�s abduction, which makes them among the most hated of the Daoine Sídhe. They do not earn many favors with the cruel pranks they play, either. A favorite prank of the Síofra is to grab a fiddle or similar instrument and play it wildly. Their draíocht is such that they can force everyone in earshot to dance against their will until exhausted. Some of the Daoine Sídhe serve the Gods, as is the case with the Murúch. Serving Manannan Mac Lír, these merfolk-like creatures are known for their dedication to the Lord of the Oceans, and also for their temperament, which is akin to that of the sea- calm one minute, violent and brutal the next. Generally, though, unless a person has angered Manannan, they are content to play in the waters and sing haunting songs to sailors. The Murúch are able to slip in and out of the undersea realm by use of a cothúlín druith, a hat which allows them passage between the worlds.

Other Daoine Sídhe are also ancestral spirits, having connections to families with some element of their blood in their veins from intermarriage millennia ago. Chief among these, and probably the most famous, is the Bean Sídhe, known to most as the �Banshee��. The Bean Sídhe is a woman of the Daoine Sídhe who appears in two forms- that of a crone, a hunched old woman with gray hair and a knowing, sad gaze, or as a lovely young flaxen-haired woman or girl who weeps and mourns as she combs her hair. She is always seen alone, and she always appears mournful and sad. The Bean Sídhe is seen as a portent of death, and is looked on by the Sinnsearaithe as a benevolent spirit rather than the evil omen of doom that the Christians see her as. She is an ancestor, one who cares for her human progeny, and is mourning the loss of one from the mortal world. "Then Cuchulain went on his way, and Cathbad that had followed him went with him. And presently they came to a ford, and there they saw a young girl, thin and white-skinned and having yellow hair, washing and ever washing, and wringing out clothing that was stained crimson red, and she crying and keening all the time. 'Little Hound,' said Cathbad, 'Do you see what it is that young girl is doing? It is your red clothes she is washing, and crying as she washes, because she knows you are going to your death against Maeve's great army.'" - Cuchulain of Muirthemne. Another way in which the Bean Sídhe appears is the Sochraideach, The Mourner, where she is heard and seen by the family in which the death will occur. She appears on the homestead or around the house of the person who is to die, and will sing a caoin for that person. Such a caoin is eerie in it�s mournful, otherworldly qualities, and is heard for three nights before the death. Sometimes the Bean Sídhe will even speak with the one who is to die, such as the case of Aibheall, a Bean Sídhe who told Árd Rí Brian Bóruma mac Cennétig he was going to meet his death at the Battle of Clontarf, and told him of his son�s succession as the Árd Rí.